We picnicked among the ruins of a city destroyed by a monstrous storm of fire and gases – the epitome of doing ordinary things in extraordinary places – and Pompeii and Herculaneum are truly extraordinary places.

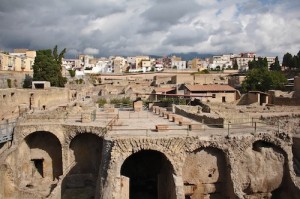

Herculaneum is right in the centre of the town of Ercolana – it’s hard to see where one ends and the other begins

Pompeii was already a thriving small city when the Romans came to civilise it and the region. Built in the shadow of the fertile slopes of Mount Vesuvius, for a time life was good. An earthquake in AD 62 left large parts of the city and neighbouring Herculaneum in ruins. The rebuilding work can still be seen in some houses, with the white lines still visible on the walls, tracing the intended final images in readiness for the painters who never came.

Many repairs were still being undertaken when the volcano spewed its deadly mess over the region seventeen years later. Tons of molten rock and ash flattened and then encased Pompeii, enclosing the city and its people in a tomb of pumice four metres thick.

It was this deadly crust that preserved so much below it and has allowed us to now have a glimpse of life and death in Pompeii. Nearby Herculaneum, in those days considered a richer and more sophisticated city, escaped the crushing destruction of the ash and pumice, leaving many more of its buildings intact, but a pyroclastic storm cloud of super-hot rocks and gases swept through the streets. This deadly surge swept through streets and homes at 160 kmph at a temperature of 500 degrees celsius like a nuclear blast, vapourising people as they tried to escape. Archaeologists have found evidence that the heat wave was so intense it shattered teeth and bones in those who weren’t instantly vapourised.

August 24th AD79 had dawned bright and clear but soon, fire rained down on the town and the surrounding area as Mount Vesuvius erupted. It certainly is one of the more ironic twists of fate that Pompeians had spent August 23rd AD79 celebrating and making sacrifice to the god of fire to ward off disaster. He wasn’t listening.

The forum at the centre of the city was as bustling that day as it is today.

Within hours it was swallowed up. Houses rich with elegant décor were engulfed, along with their owners and even animals. Buildings collapsed under the sheer weight of the debris.

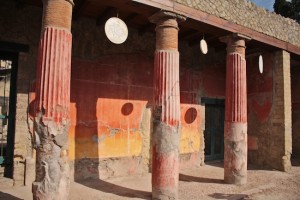

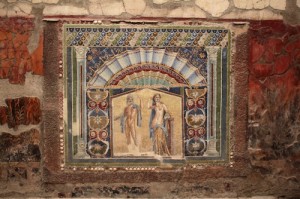

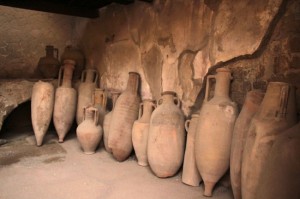

In Herculaneum the rocks and gases flowed through the city streets, filling the building from the bottom up. Fortunately for us, the rubble supported buildings rather than collapsing them and we can see far more detail and examples of second storeys than in Pompeii. Even wooden beams remain, as well as a host of artifacts; many are now now stored in the Naples Archaeology Museum.

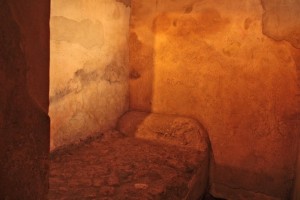

The upper floor of a merchant house, with charred timbers, wall paintings and the brass corner of the bed still entacted

These incredible historic sites tell us the story of everyday life in Roman times – how people lived, what they ate, the success of freed slaves, the lives of the rich and poor, almost side by side.

The contrasts are as fascinating as the similarities. In Pompeii the roads filled with sewage and stepping stones were built to avoid the filth. In Herculaneum a strong porters union meant wagons were banned from the centre and only donkeys or porters allowed. The lack of stepping stones might suggest their hygiene was better too.

Deep grooves show the wagon tracks. Large stepping stones sit above the ruuning open sewers that were the streets of Pompeii

The two cities have taught archaeologists much about Roman life, from the temples to the much more temporal!

It is not surprising perhaps that one of the most visited buildings in Pompeii is the Lupanar, or wolf’s den – the main brothel. The queue outside today is probably longer than when it was a thriving business, but the amount of time you have to linger and admire what is on offer, is much shorter.

Frescoes above the tiny rooms depict the services supplied on the small stone beds. Pompeii was a cosmopolitan city, with many foreigner traders who did not speak the language, but clearly understood what was on offer from the pictures.

The brothel is not the only place where erotic imagery can be found in Pompeii, in fact they seemed rather fond of it.

Not quite a welcome mat, but clearly a cheery hello! This erotica was placed right at the front door of the merchant’s house

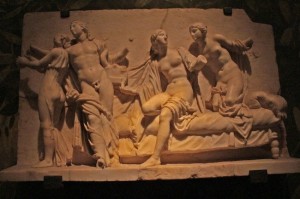

Certainly it did not attract the prudery and censure that it did in later years. The Secret Room, or Cabinet in the Naples Archaeology Museum held a vast collection of erotic art, but was for privileged eyes only. It is only since 2000 that it has been open to the public!

The Roman erotic art distinguished men from women by skin colour – you would think there were other clues!

The Secret Room in the Naples Archaeology Museum is full of erotica and was kept locked until quite recently

The excavations tell us how the people of Pompeii and Herculaneum loved and lived. Letters written by Pliny the Younger, who observed the event from across the Bay of Naples tell how the volcano erupted and how the people died:

a darkness came that was not like a moonless or cloudy night, but more like the black of closed and unlighted rooms. You could hear women lamenting, children crying, men shouting. Some were calling for parents, others for children or spouses; they could only recognize them by their voices. Some bemoaned their own lot, other that of their near and dear. There were some so afraid of death that they prayed for death. Many raised their hands to the gods, and even more believed that there were no gods any longer and that this was one last unending night for the world.

The Pompeii site is huge – it is almost impossible to get around it in a day. Herculaneum, in contrast, is only a few city blocks and is restricted by the very fact that it is in the middle of Ercolana – the modern town that wraps itself around the ruins.

It is, however, better preserved in many areas.

As with Pompeii, many of the original mosaics and murals are on display at the Naples Archaeology Museum. The sheer scale of the treasure reclaimed from these two volcanic tombs is incredible.

While the museum now houses most of the findings from the sites, the original excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum did not go well. Normally artifacts were retrieved, but the site left open to the elements once more.

In recent decades much more work is being done to preserve the site as well as the content.

Today one of the biggest problems the archeologists face is the extreme weather and heavy rainfall that has affected the region in recent years. Millions of euros are being spent simply trying to keep the site from becoming waterlogged. It seems nature hasn’t finished with Pompeii and Herculaneum yet.