Robert Burke and John Wills’ ambitious expedition to map Australia from the south to north coasts in 1840 is a classic saga of bad planning, worse leadership and fatal consequences. Yet the two men are still memorialized in Australian history.

Finding a way through Australia’s harsh terrain from Melbourne on the south coast of the continent, to the Gulf of Carpentaria in the north – more than 3,000km – was a much prized goal.

Every colony, which have since become states, was considering the attempt and putting up considerable money for the victorious team.

So today it would seem strange that the financial backers of the Victoria expedition committee still chose the entirely inexperienced Robert Burke to head it. But factions within and dislike of “foreigners” on the committee, despite their expedition experience, meant local policeman Burke got the gig. It was a decision that proved fatal.

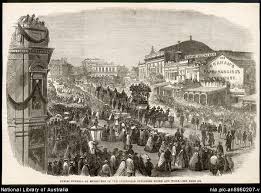

The signs were there from early on. Burke’s team of 19 men left the Royal Park in Melbourne in August 1860 with six wagons of supplies to last two years.

The committee had also decided in their wisdom that dried meat carried in three extra wagons, was a better idea than the normal practice of herding live cattle, which can move on their own and be slaughtered en route. Apparently an oak writing desk was also amongst the necessities loaded onto the creaking vehicles. One broke down before it even left the park; a second was lost within a few kilometers.

It took the team two months to travel 750km to the edge of what was still the colony of Victoria. The postal service usually took a week to travel the same route. By that time two of the expeditions five officers had resigned because of Burke’s leadership, making John Wills second in command; 13 men had been fired and 8 newly hired. It wasn’t looking good!

Because of fears that other explorers may beat them to the coast and claim the prize money, Burke decided to make a dash to the Gulf with Wills and team member John King, despite the journey being through the worst of the Australian summer in the outback. The rest of the group was left behind at a depot camp near Innamincka.

More bad decisions, illness, failing supplies and impassable swamps meant Burke’s team never made it to the coast and only three of the four made it back to the original camp, only to find the remaining team had left hours earlier. They had waited an extra month for the men to return, but finally given up hope, leaving supplies and instructions to “Dig” for them.

The Dig Tree is the last story in their catalogue of failings.

After using all the supplies, Burke and Wills made the final fatal judgement – deciding to make a 250km desert trek west to a stock station instead of retracing the steps of the depot party heading south. They left no message at the tree, so when the depot party returned with fresh supplies they did not know that the two men were only 35km away in the wrong direction.

Burke, Wills died within a few days and a few kilometers of rescue, ten months after they set out from Melbourne. In all seven men perished in pursuit of the prize. Perhaps the final insult of their failed endeavour is that the rescue party sent out to find the two men from competing colony of Queensland, because there was no sign they had been at the Dig Tree, kept on going north on their search and went on to successfully make the north-south trek and claim the prize money.

But because history and people are strange, it is still Burke and Wills who are remembered, despite their failure, and not that other guy who actually completed the mission.

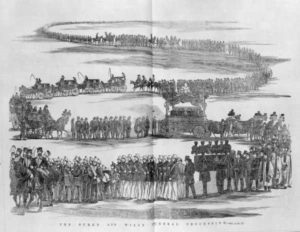

Thousands lined the route for their funeral procession.

Their names are in every Australian history book. Statues, memorials, roads and monuments carry their story

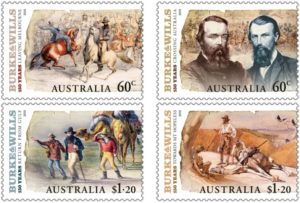

their faces even ended up on the nation’s stamps.

So perhaps in some perverse way, they succeeded after all.