Modern technology has given us electric cars and rockets to Mars, but you still can’t beat driving a classic old outback track across Australia, in a quarter century old 4WD!

The outback tracks in Australia were predominantly stock routes – some were more “official” than others

Having finally made it across from the east coast on The Big Detour, out first Aussie outback track was, strangely named after a Polish explorer. But what an explorer! Pawel Strzelecki was about as different from Australia’s famously failed adventurers Burke and Wills as you could get.

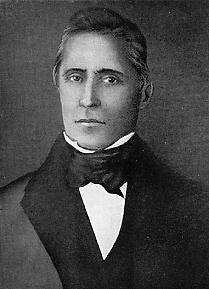

Born of noble stock in Poland he became a notable explorer, navigating his way around North and South America, Europe, Africa, Cuba and many south Pacific islands before arriving in Australia in 1839.

While in Australia he explored and surveyed vast areas of Gippsland and the Snowy Mountains – climbing and naming Australia’s highest Mount Kosciuszko in honour of a national hero in Poland. He mapped Tasmania, mainly travelling on foot and in all covered 11,000 kilometers of New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania. He eventually left for England via China, the East Indies and Egypt and on arrival was recognized by the Royal Geographical Society.

Strzelecki did much good work in his life, including coordinating famine relief in Ireland and was given many awards. It is not only the Track that bears his name in Australia, but also a desert, a mountain range, a mountain, a peak, a creek and a highway.

It is ironic that the Track which is named after such an upstanding man was actually mapped out by a thieving bushranger.

Harry Redford was working a cattle station in Queensland which was so large that he realized the owners wouldn’t even notice if some of their cattle went “missing”. Over a three month period in 1870 he corralled and then drove 1,000 cattle through some of the harshest outback lands, including carving a track through the Strzelecki Desert. His 1,000kilometer journey was so impressive and audacious that when he was finally caught, the jury acquitted him.

Thankfully we didn’t have any cattle to herd and these days on a good day the Strzelecki Track could be driven at 100kmph in a Toyota Camry.

Even the road trains steam through – leaving their mark on everything they pass!

But on a bad day it can’t be driven at all. We had a good day to start with, but spotted a few signs of what it can be like on a bad one.

And then we found out how little it takes for it to be a bad one.

Just a spit of rain turned the baked earth into sloppy, cloying mud. Much more rain and we would not have made it through.

But like Strzelecki and Redford, we finally got to the other end, sliding into Marree, mud-coated and ready for our next classic track.

Marree is the start of the Oodnadatta Track – an historic outback town that is proud of its history.

The Oodnadatta Track from Marree to Marla is another Australian touring legend. Named after a small town along its stretch, the track is a dirt road running more than 600km to the centre of Australia. It follows ancient Aboriginal ochre trading routes and it is easy to see why.

Much of the track runs parallel to Lake Eyre, which you can read and see more of in our previous blog “ Lake Eyre from the Air”.

As well as the wonders of the Lake, the semi desert track holds many surprises.

Plane Henge is a sculpture park 70 kilometers into the desert with planes, parts of trains and automobiles fashioned into glorious quirkiness.

Man-made curiosities were almost outdone by the natural ones. Far below the sand and red earth is the Great Artesian Basin – a massive underground natural water supply and system. Every now and then along the Oodnadatta Track the underground comes overground.

The Wabma Kadarbu Mound Springs are an oasis of softly bubbling calm literally in the middle of nowhere.

They are part of a string of springs through the region that were used by Aborigines for generations. More recently the easy access to water was the rationale for running the iconic Ghan railway line and overland telegraph through the region.

The old Ghan line is long gone, but its ghost remains all along the track.

Sometimes the good times roll again. One of siding shed is now famous for its annual outback new year’s even ball, but for most of the year the sands are slowly taking back the land.

One man-made structure that is still maintained through the desert is the Dog Fence. The Dog Fence is the longest fence in the world. This humble stretch of wood and wire first built in the 1880’s is one of the longest structures in the world. Designed to keep dingoes away from sheep stock, it runs a mind-boggling 5,614km from the east to the south of Australia. And that is a couple of thousand kilometers shorter than it used to be!

Hundreds of men live along the fence, working in shifts and sleeping in small huts complete with satellite TV and shortwave radios to keep the barrier intact.

Our Oodnadatta journey ended just over half way up the track. We spent five days at William Creek, flying over Lake Eyre and helping out at the local pub. From there we turned off the Track and took the shorter Coober Pedy Track to the opal-mining town of of the same name. The Living Fire is the fascinating story of that strange mining town. We fully intend to return and finish the last stretch one day.

We’ve seen emus, roos and critters galore.

We have watched eagles soar on the endless thermals across a huge sky. We have battled lashing rain, all-enveloping, choking dust storms, energy-sapping heat and many, many flies.

About the only thing we saw on the whole journey and once he passed we couldn’t see very much at all

We rarely saw another human soul until we get close to a town and even then they are few and far between. But it is those hardy men and women from generations past, and the tough old buggers that still call the outback home who have made our recent journeys across the old stock tracks possible and so memorable.