This humble little lump of woody fibre that takes decades to create and more often than not, is then just tossed in the bin overnight, is worth a second glance.

The majority of the world’s cork production is in southern Portugal, so we got the chance to do just that.

It generates one of the most diverse ecologies in Europe, gives employment to 60,000 people, stops up 60% of wine bottles, is fire retardant, impermeable and it floats – not much can compare to cork for its diverse range of uses. It takes about 25 years for the cork oak to be ready for its first harvest. The bark is then carefully peeled off with a special axe, leaving a deep red trunk behind, which eventually dulls to brown over the years.

The first harvest is thought to be of lesser quality and is called “male” cork. The good quality material comes after the second or third harvest and is rather evocatively known at “gentle” cork. A harvested tree is left to rest for ten years between each peeling and lives for around 200 years.

It’s a two billion dollar industry that only ever seems to be seen growing on small acreages, on the sides of the road, in small yards and family farms.

Cork production has been hit by the use of screw tops in the wine industry, but the versatile cladding is determined to keep afloat. Corks’ green credentials have helped its PR push – the low carbon footprint and sustainable harvests, as well as the natural habitat it nurtures – who could possibly prefer metal! Any Australian couldn’t help but feel at home in the cork forests of Southern Portugal – as they grow alongside huge Aussie gum trees, giving off a great eucalypt scent as you pass through.

Corks aren’t just for bottling – although that is this the primary usage – it has been used in musical instruments, shuttlecocks, heat shields, laser printers, transmission systems, a boat (honestly – 165,321 wine corks=one boat ), fishing floats, and even fashion.

Its impermeable and thermal properties make it useful in the house and building trade, as waterproof flooring, table mats, mixed with concrete to give better insulation or even just raw.

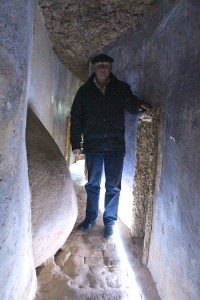

The Convent of the Capuchos, or Cork Convent in the Sintra hills above Cascais, was built in 1560 for Franciscan monks, and uses the bark extensively as cladding, chairs, doors and window linings.

The convent was intended to keep faith with the notion of simplicity and being at one with the natural surroundings.

If you want to see what austerity measures looked like in the 16th century, then have a prowl around Capuchos.

The melding of rocks, trees and earth into the fabric of the buildings doesn’t get much closer to nature.

So, next time you pop a cork, we hope you have a new-found admiration for the stuff that can float boats, warm houses, dress you and keep your food and drink fresh – we’ll raise a glass to that!