Are you stuck for the ideal romantic gift, something that will last a lifetime and also be a daily reminder of your affection? Why not forge your love in steel?

Just south of Canberra is the Tharwa Valley Forge, where Karim Haddad has honed his exceptional craft and now teaches courses in the art of Japanese knife making.

He promised to help us make knives that will last 100 years.

His passion for his work is obvious and infectious. His 12-year-old daughter Leila is already a renowned artist who is the darling of the Japanese knife-making scene.

We too are now converted. So how does such a love affair begin?

Well, on day one it all looks very unassuming to begin with. The studio where much of the work takes place looks very orderly and there is no hint of the sparks that will fly, or the grinding, filing, cutting and drilling to come.

Also on hand to help is Dean Jard – a cut-throat razor expert who sharpens his blades under a microscope!

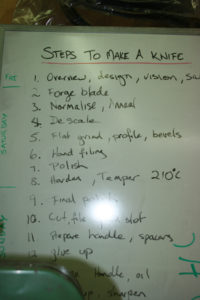

Paper, plastic and a pencil are our initial weapons of choice, selecting the type of knife you want to make, drawing out a template for the blade and measuring your hand for a handle perfectly sized to you.

Then it’s time to get all fired up at the forge! Steel bars are heated up in a small but perfectly formed gas-fired forge known as a pig. Though she be little, she is fierce – pumping out 1000C. It is vital to work the metal as fast as possible, hammering and stretching the metal before it quickly turns back to grey hard steel.

But the heat is fleeting and the beating needs to be fast and furious before the embryonic blade has to be plunged back into the furnace.

After repeated firing, hammering and cooling – the normalising and annealing process – the excess steel is cut off and the remainder is starting to take shape, but looks like a blackened, carbonised mess.

The blackened blade is blitzed on a grinder to remove the carbonized coating,

and then is ready to be tempered. Once more into the pig, but at a lower temperature (a mere 210C) and then soused in oil to cool it at speed.

After the final treatment, which rather unexpectedly consists of lining up the gnarly looking steels on a baking tray and popping them in the kitchen oven for an evening bake, day two dawns, with Karim having given an overnight initial polish and what yesterday looked positively bronze-age is starting to look like the heirloom we were hoping for.

But now the heat is on in a very different way. Creating the final finish on the blade sounds easy, but this is no ordinary process.

It starts with a belt sander, and works its way through finer and finer grade sanding, draw-filing (dragging fine paper endlessly one way down the length of the blade and then polishing or linishing with the finest paper and then cardboard until there is no sign of any mark, flaw, line or blemish. It’s back-breaking, relentless sweaty work in 40C heat but Karim will not let you stop until the blade is perfectly smooth to the touch and his keen eye.

The blade is then covered in blue tape for protection while we turn our attention to creating the handles. Much like the uninspiring lump of steel that we began with, the buckets of woody chunks and slabs show little of their potential and none of their final promise.

The main blocks are married with smaller pieces, which form the guard and slivers of metal and cardboard that make up the dividers. It all looks like something from a kiddies craft class, especially when the gluing, sticking and clamping happens.

But then we bring out the sanding big guns, and the handles start to show hints of colour and form.

It’s not until the last moment when the oil is applied to the handles that the final magic happens and our heirlooms blossom into life.

We love our knives. We are proud of what we have created. Japanese chefs believe our soul goes into our knives once we start using them. What better gift could you give than your soul?