Uluru stands 350 metres above ground and sits up to six miles below. It is spectacular, but on this continent of extreme nature it is not alone in its grandeur, scale and drama.

Light and shadow is cast by the passing clouds

Formally known as Ayers Rock, Uluru is, to get technical, an inselberg. To be more evocative, that translates literally to – an island mountain. Long before you see it in its entirety, it dominates the skyline.

Looming on the horizon

The rock

Even the wide angle lens doesn’t do justice to the scale of Uluru

It is nearly 9.5km in circumference. A mammoth sandstone rock in the middle of the desert, it is considered sacred by the Aboriginal people of the area and has captured the imagination of the millions of visitors who have come to gaze on its vastness over the years.

One of the many faces of Uluru

The black streaks and dimples become waterfalls and wells during the rains

The colours are every changing with the sun and the clouds

There are many differing Aboriginal stories of how the rock came to be, but regardless of which version, it is now one of the most recognisable nature wonders of Australia. It is famed for it ever-changing glorious red and golds as the sun drifts up, over and down its surprisingly smooth faces.

Watching the sunset at Uluru is one of the must do events of a visit. With the solid constant presence of the rock beyond the trees, the crowds swell and jostle for prime photo positions.

The crowds gather for sunset

We were fortunate enough to spend the time with old friends. Mick and Rusty were at the Army Apprentice School with Geoff back in the day. We tagged along with Mick, his wife Sue and kids Jack and Georgia (aka Buzzard and Possum) and Rusty and Marg for a week of their holiday. Thanks for letting us gate-crash the party guys!

Rusty and Marg Playford

Mick, Sue, Jack and Georgia Poxon

Us at Uluru at sunset

And then come the colours.

The red rock glows with fire as the sun dips

A pinky blue backdrop to the sunset

How many photos can you take of a rock at sunset? A lot!

As the rock colour fades, the sky lights up

Sunrise is just as popular. Around on the opposite face early the next morning the coffee and cameras were at the ready.

Colours of morning

Everyone is ready to greet and photograph the dawn

The first morning blush in the sky and on the end of Uluru

Even the trees take on the morning glow

Sunrise over the rock, with the Olgas in the distance

The colours are perhaps not as dramatic and the night before, but that great rock still manages to capture your breath, and make you feel that magic is about to happen.

Uluru/Ayres Rock has not always been a happy place. There was the famous case of Lindy Chamberlain who fought a long court case to prove that a dingo and not she had killed her baby at the Rock.

For many years the local Aboriginal community claimed they were the traditional owners of the land and Uluru was theirs fought to be recognised as the rightful guardians of the area, and in 1985 the rock and the surrounding lands were finally handed back to them.

Thirty five people have died trying the climb the rock.

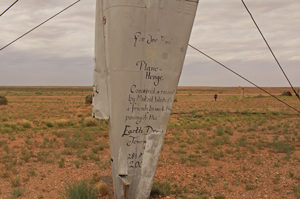

Testimony to some of those who have died climbing the rock

No photo can do justice to the difficulty of the climb and the steepness of the smooth rock face. A chain has been put in place for many years to help those who take up the challenge.

The climb to the top is a lot harder than it looks

The climb is so steep that you need to pull yourself up on the chain

The Anangu Aboriginal people of the area, for whom the rock is sacred, request visitors not to make the climb and often nature puts a stop to it anyway, with high winds or low clouds making it even more dangerous and the chain is closed.

The request from the traditional owners not to climb, in front of the chain for the climbers

But many still do and the views from the top are reportedly spectacular.

Walk the line

As soon as the climb is open, people climb

The views from the base are pretty amazing. A 10km walk all around the rock shows the different faces and sacred places of Uluru. We thought we might ride it on hire bikes, but at $45 each, we decided a leisurely stroll was more our style!

Even the trees look ancient

Aboriginal stories and information feature all around Uluru

The walk around the base of Uluru

The waterhole

The walk to the waterhole

From waterholes to surprising amounts of lush vegetation, and the more than twenty different species of animal that live and thrive on this lifeless looking rock, it is truly a special place worthy of its World Heritage Site status.

But it is not alone. Not far from Uluru is Kata Tjuta or the Olgas. A group of sandstone mountains even higher than Uluru and also part of the sacred dreaming and meeting places of the local Aboriginal people.

Kata Tjuta, the Olgas in the early morning haze

Kata Tjuta or the Olgas are also spectacular and hardly get a mention outside Australia

The highest point of Kata Tjuta is more than 200m higher than Uluru

There are 36 domes in all, spread over nearly 22 km2 and while Uluru gets all the attention normally, the highest of the three dozen, Mount Olg – at 1,066m – towers over the Rock.

Like Uluru, there are many Aboriginal legends around the creation of the domes, but many are not told to outsiders, especially women, as much of the site is considered “men’s business.

Looking up on of the sheer walls of Kata Tjuta

Mount Olga

Walking through one of the gorges at the Olgas

South of the Uluru / Kata Tjuta national park is another monster monolith – Mount Conner. With such illustrious near neighbours Mount Conner doesn’t get much press, and if you are coming up from the South it is often for people the first tantalising and incorrect glimpse of Uluru. But Mount Conner is pretty impressive in its own right, so we wanted to give him some space amongst the big ones.

Mount Conner

Uluru and the Olgas may get the “being the biggest prize”, but Kings Canyon not only has size and scale, it also has a hike that boasts a 100m climb affectionately known as Heart Attack Hill, before you reach the rim. Once up there you are greeting with a reassuring defibrillator and emergency radio beacon!

The beginning of the climb up Heart Attack Hill

Heading up Heart Attack Hill

Just in case Heart Attack Hill lives up to its name

There’s still a long way to go

Thankfully we didn’t need the machine, and the five hundred roughly hewn steps we had toiled up lead us onto the top of the canyon and a six kilometre walk, scramble, hike over ancient stones and a landscape that has remained unchanged for millennia.

Just for scale – the tiny white dot in the centre is a person!

Vast vistas

The cliff faces of the canyon are weathered over endless time. Some have had more recent rock falls, which have left spectacular slides behind.

Remnants of the last wall slide

Dramatic landscapes

Layers of time

Kings Canyon is an important watering hole in the harsh Red Centre of Australia. Little wonder that the waterhole and towering trees at the base of the gorge is called the Garden of Eden.

The Garden of Eden on the valley floor

More than six hundred species of animals and plants live in the Canyon, taking shelter in the vast gorge and enjoying the Garden.

Looking toward the Garden of Eden, with the black outline of the steps across the gorge

Looking along the curve of Kings Canyon

Flowers and berries feed the many birds and animals that live in Kings canyon

Bowed and ancient

Kings Canyon is a key water source in the area and the River Gums know it

Nature will always find a way to flourish

It is surprising how much grows on what seems like barren rock

The Lost City is another area of the Canyon Rim – with towering walls and stunning natural formations, including solid rock, still rippling with the traces long-forgotten streams.

Where the river once ran through it

The climb opens out into a natural amphitheatre

More recently tourism has brought a boom to the area. Cotterill’s Look Out is named after one of the Red Centre’s early pioneers of tourism to the region – Jack Cotterill.

Crossing the bridge to Cotterill’s lookout

Looking across to Cotterill’s Look Out

While Uluru and Kata Tjuta and Kings Canyon may be a relatively new find for tourists, local Aboriginal people have lived and thrived in each place for more than 20,000 years and they rugged rocks, canyons and mountains are still important sacred areas for them. After visiting all three it is easy to see why.