Perched higher than the swallows flit, warnings abound that visiting the castles on the cliff tops in strong winds is very dangerous and during storms is strictly forbidden.

They also say the steps are slippery; the climb is steep. But who cares about all that, when thousands of years of history await us at the top.

Even the names of the chateaux of Queribus and Peyrepertuse sound magical and the views are breathtaking.

Hewn from the rocky outcrops as defensive positions, it is incredible to realise that the first mention of the castle at Queribus is in 1020. For us modern crusaders, it was a steep, panting, sweaty 250 metre walk from the car park – minus armour and sword! We had already been grateful that Charlie Charleston had managed the winding two kilometre drive on a 17% gradient! Imagine being one of those sorry souls who had to build this granite eagles nest!

At 728 metres high, Queribus was the guardian of the mountain pass of Grau de Maury and sits, seemingly precariously, on a ridge overlooking vast swathes of Corbieres, Fenouilledes and the Roussillon Plains.

As with most castles, it’s history is chequered, starting in the hands of the Count of Besalu, who served the Count of Barcelona, who became the King of Aragon – part of modern day Spain. The castle gave shelter to the religiously persecuted Cathars and is often cited as the last Cathar stronghold before falling to the French in 1255, during the Albigensian Crusade. The history of the Cathars is fascinating and not widely known outside this region. It’s worth a read to find out about their history and ideology on equality, peace, vegetarianism. Easy to see why they posed such a threat to society and could justifiably be hunted down and massacred by order of the Catholic pope.

Meanwhile, back up the mountain, the French put their new prize to good use, making Queribus one of the “Five Sons of Carcassonne” a group of castles central to the French defensive system against the Spanish.

Like Queribus, its near neighbour Peyrepertuse was one of the Five Sons of Carcassonne. Eleven kilometres as the crow flies (if he would fly that high) and a couple of valleys over, Peyrepertuse stands higher, at 800 metres, and is an even larger complex, linked by a huge stone staircase. The stairs were commissioned by the French king Louis IX and were not made from pre-quarried stones, but rather chiselled out of the very rocks of the limestone ridge the castle clings to. Despite never once lifting a hammer to help, St Louis got the staircase named in his honour.

Peyrepertuse has all the proper castle trimmings of towers, dungeons, long drops, chapels, spectacular views for spotting potential marauding hordes and of course, a bloody history.

The site has been occupied since Roman times, from the start of the first century BC. Since the first official mentions of the Castle in 1070, ownership has ping-ponged between the kings and countries of Spain and France, before finally becoming fully French-owned in 1240, when it took on its prime defensive duties with its four Carcassonne castle siblings.

Getting to Peyrepertuse is even harder than Queribus. Once again Charlie championed us to the car park, but from there it was more like a scramble through a Hobbit woodland path for parts of the climb and then a gut-busting hike up countless stone-shod, uneven steps and rock piles to the entrance, balanced on the top of the almost dragon-like spine of the ridge, that looks barely wide enough to support it.

While the history of both of the castles is ancient, restoration work was only began in the 1950s and was pretty limited in its scope. Serious restoration of Queribus only started in 1998. Even post-restoration the sites would probably not pass a health & safety inspection in the UK or Australia, with their rubble-strewn climbs and hand-rail free steps. But to climb that ancient route, to clamber over the warm stones and get just a hint of life in a millennia gone by was worth all the effort.

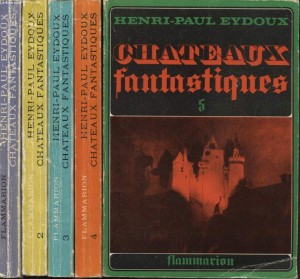

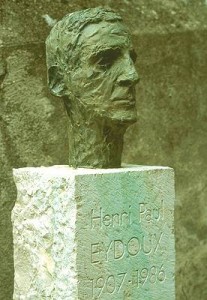

Much thanks is due to one passionate and prolific man for making these castles available to the public. Henri-Paul Eydoux, historian, resistance fighter, diplomat and author, translated his passion for the ancient history of France into a series of books called “Chateaux Fantastiques” in 1969 and a campaign to have them restored and opened to the public.

Fittingly, he is buried in a cemetery at the foot of the Peyrepertuse castle hills.

This story and images are for you Mr. Eydoux, with our thanks.

at 3:28 pm

Oh I’m so jealous. The stone work must be amazing. Glad to see Charlie’s still good.

Chris.

at 11:43 pm

WOW !!! Can I get there by helicopter? leaves my “scary roads” looking like super highways. Absolutely facinating history and fantastic photos. Love from Mum